Michigan Trip Day #3

Monday, September 1, 2025 (Labor Day)

We read that the dark color of the water is not because it is “dirty,” but rather because of minerals dissolved in the water.

The park had fantastic paved walking trails and an elaborate boardwalk that allowed viewing the river and falls from multiple levels.

In addition to the museum, the grounds also allow for access to the beach. The beach was surprisingly sandy with sand we would have equated more with the Caribbean. However, at the juncture of the sand and the water there are rocks which have been ground smooth from tumbling in the surf. The woman on the left was looking for agates, and tried to teach me what to look for - it was a lost cause. But, I did get to dip my toes into the 65 degree water of Lake Superior - refreshing….

[Click on Image for Map]

And, of the artifacts from the Fitzgerald, the most impressive is the ship’s bell which was raised in 1995; twenty years after it sank on November 10, 1975. The bell now resides in the museum as a testament to the 29 men who died in the wreck. The bell was replaced with another, engraved with the names of the 29 men lost. It now serves as a grave marker 530 feet below the surface of Lake Superior.

The bell in enclosed in a glass case so it cannot be touched. However, after this bell was raised from the bottom, a ceremony was held and a member from each family of those lost on the ship came forward and rang this very bell in honor of their loved one. Powerful stuff!

The documentary movie they show about raising this bell was really something and the emotion was palpable.

These artifacts were recovered from one of the Fitzgerald’s lifeboats. However, the lifeboats were found heavily damaged and showed no signs of being used. It is believed the vessel sank so rapidly that they never had time to deploy the lifeboats. Rather, they came loose when the ship sank and collided with the bottom.

Here are some flares, a flare gun, a lantern and some matches. None of which were ever used.

This is the bell recovered from the SS Daniel J. Morrell which split apart in a strong storm on Lake Huron on November 29, 1966. One man, by the name of Dennis Hale, survived this disaster and was able to tell the story of how the 603-foot freighter broke in two.

This was the clock on the wall of the Daniel J. Morrell which appears to have stopped working at 03:27AM, marking the time the ship sank.

This is the rudder from the M.M. Drake, a 201-foot wooden schooner, which sunk six miles west of Whitefish Point in a storm on October 2, 1901.

A Fresnel lens typical of the one used at Whitefish Point.

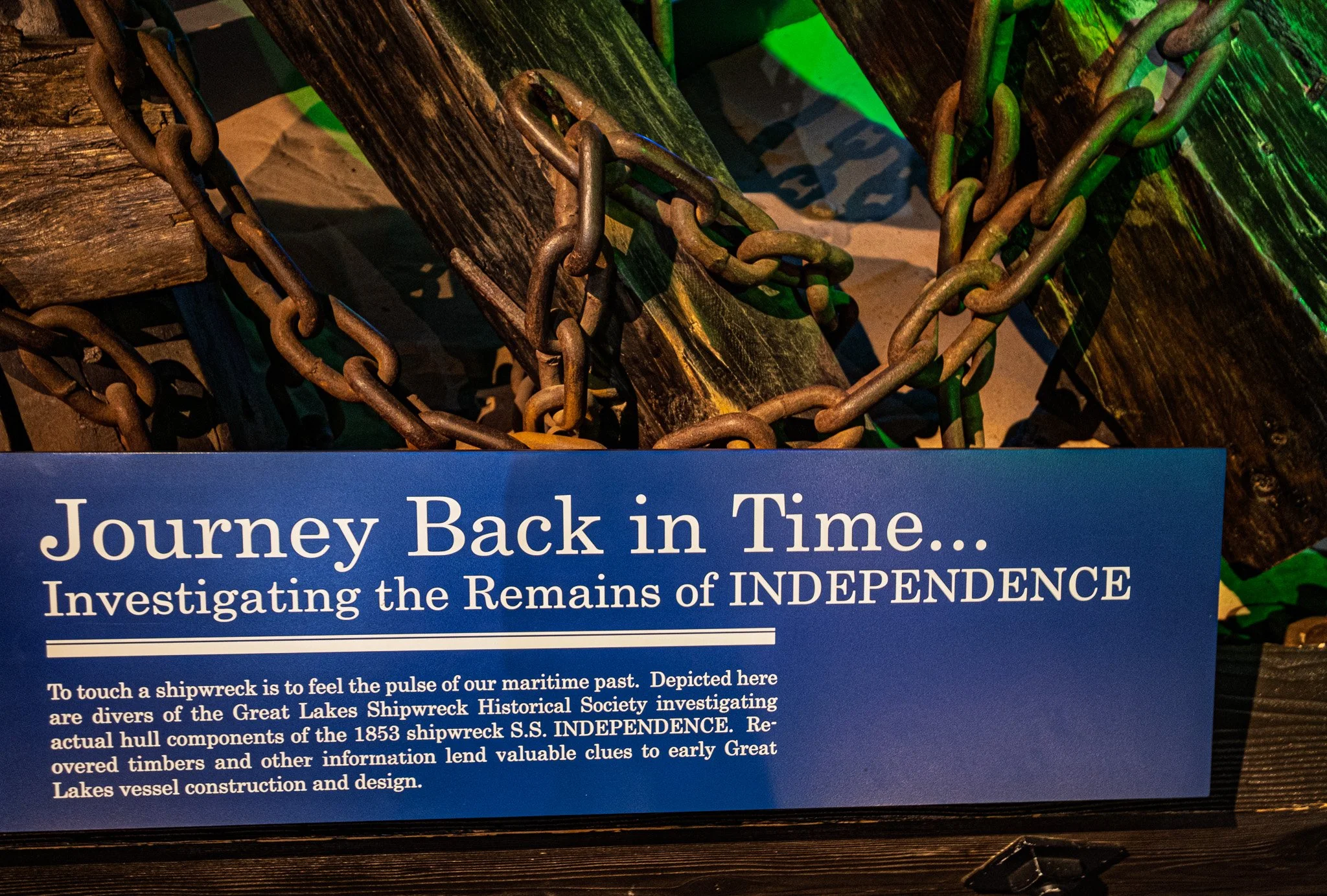

These next few are some of the interesting exhibits throughout the museum. They are worth taking a few minutes to read.

This was brilliant in the early 1900s!

Having driven through the thick fog on the morning we visited the museum, we can attest that some non-visual means of alerting ships was imperative! This was an absolutely brilliant solution for its time.

German spy!

Another Fresnel lens, this one is a “fourth order” lens; which denotes its size. The largest ever used on the Great Lakes was apparently a “second order” and we will see that next.

This monster is a “second order” Fresnel lens and was the largest ever used on the Great Lakes.

The lens is 9-feet in diameter and weighs 3,500 pounds. It floats on a bearing surface of liquid mercury, which allows for near frictionless rotation.

This lens was located in northern Lake Michigan and warned ships of the shallows known as White Shoal. The light it projected could be seen at a distance of 28 miles.

The lens was rotated using a pendulum mechanism, much like an old grandfather clock, and the pendulum was on a 44-foot cable. The lighthouse keeper had to wind the mechanism every 2 hours and 18 minutes and this resulted in a rotational speed which produced a distinctive 7 ½ second pause between each visible beam of light.

Early diving suit used to explore shipwrecks. We agreed this was NOT a job we would have taken at any price!

The medical requirements for diving using this suit.

Repeated venereal disease - but apparently just one case of syphilis doesn’t disqualify you! I know at least one of my Residents would be happy to hear that…. ;-)

This exhibit of the Independence - as well as serval other exhibits - actually allow you to touch the wreckage and artifacts which were recovered from the bottom of the lakes. Fascinating to know you are actually touching such a piece of history.

This image is taken from the beach on Whitefish Point. To the left is the open water of Lake Superior and on the right is the relative shelter of Whitefish Bay. Ships are relieved to reach the shelter of Whitefish Bay when they encounter November storms on Superior. The Edmund Fitzgerald lies 530-feet below the surface only 15 miles from this point - in Canadian waters.

[Click on Image for Map]

One final look back at the lighthouse before heading to the Soo Locks.

As is so typical and consistent, the grounds of the locks are always so well maintained by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers.

This is a large piece of the rock containing iron ore which is mined in Minnesota and Wisconsin and made into the taconite pellets so often carried by the Great Lake freighters. It was 29,000 tons of taconite pellets that the Fitzgerald was carrying when it sank in Superior on its way to these very Soo Locks on November, 10, 1975.

This plaque in the Soo Lock Visitor Center explains how each time the locks raises or lowers it requires the movement of 22 million gallons of water!

So, for this one small up-bound fishing boat, it took 22 million gallons of water to raise it from the level of St. Marys River to the level of Superior.

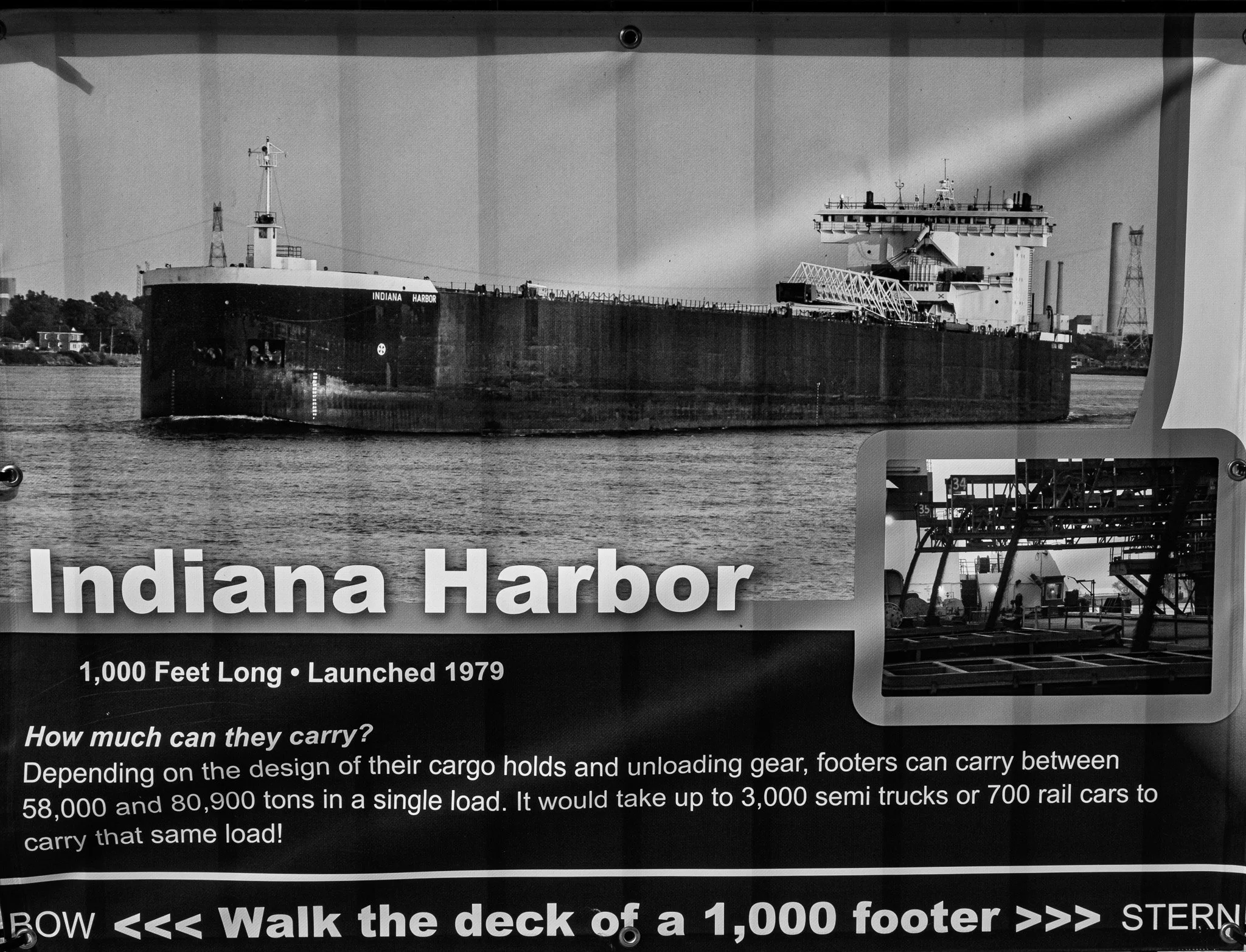

In the Visitors Center they have a board that indicates when the “footers” are scheduled to arrive at the locks. A “footer” is the term they use to denote a freighter of 1,000 feet in length. The board indicated that the Indiana Harbor was up-bound in the next 30 minutes; so, naturally, I had to see that!

There are apparently 13 “footers” that pass through the Soo Locks and they had a poster for each one hung along the fence. This is the poster for the Indiana Harbor - which was headed our way.

The Indiana Harbor up-bound from St. Marys River into the Soo Locks and eventually onto Lake Superior.

Slowly working its way into the locking chamber.

The Pilot House is almost completely in the chamber.

All 1,000 feet of this amazing ship is now in the locking chamber.

As a point of reference, the Edmund Fitzgerald was 729-feet in length - which was one foot shorter than the maximum allowed in these Soo Locks when it was built in 1957.

Fully lifted and awaiting the O.K. to exit into Whitefish Bay and Lake Superior.

As much as I would have loved to stay and watch it completely exit the locks, the light was fading and we still needed to make it to Mackinaw City - and ideally cross over the Mackinac Bridge while it was still light out.